The Runaway Slave Who Took the 'Underground Railroad' from the Mississippi to... Heywood?

‘My name is John Brown. How I came to take it, I will explain in due time. When in Slavery, I was called Fed. Why I was so named, I cannot tell. I never knew myself by any other name, nor always by that; for it is common for slaves to answer to any name, as it may suit the humour of the master. I do not know how old I am, but think I may be any age between thirty-five and forty.'

|

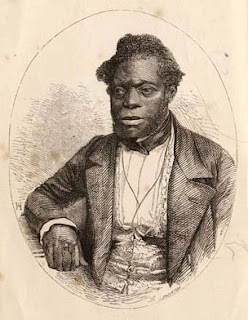

John Brown, 1855.

|

Brown had been born as 'Fed' sometime around 1810 in Southampton County, Virginia, on the plantation estate of Betty Moore. His slave parents Nancy and Joe had three children, the other two being twins Silas and Lucy, before Joe was taken elsewhere when his master moved house. It was the last they ever saw of him. Joe’s father had been taken from Nigeria and was of the Igbo people. Young Fed only remembered seeing him just once, and recalled him being ‘very black’. With her husband gone, Nancy married another man and had a further three children. Their living quarters were basic:

‘We all lived together with our mother, in a log cabin, containing two rooms, one of which we occupied; the other being inhabited by my mother's niece, Annikie, and her children. It had a mud floor; the sides were of wattle and daub, and the roof was thatched over. Our sleeping place was made by driving a forked stake into the floor, which served to support a cross piece of wood, one end of it resting in the crotch, the other against the shingle that formed the wall. A plank or two across, over the top, completed the bed-room arrangements, with the exception of another plank on which we laid straw or cotton-pickings, and over that a blanket.’Most of the Betty Moore estate (including the slaves) was divided among her children when the youngest of them married. The impending separation was met with dread by the slave population, terrified that their families would be forever split apart.

‘The women who had young children cried very much. My mother did, and took to kissing us a good deal oftener. This uneasiness increased as the time wore on, for though we did not know when the great trouble would fall upon us, we all knew it would come, and were looking forward to it with very sorrowful hearts.’The slaves were divided into three lots of 25-30 people, drawn by lot from a hat. Fed and his mother were to be separated from the twins.

‘By about two o'clock, the business was concluded, and we were permitted to have the rest of the day to ourselves. It was a heart-rending scene when we all got together again, there was so much crying and wailing. I really thought my mother would have died of grief at being obliged to leave her two children, her mother, and her relations behind. But it was of no use lamenting, and as we were to start early next morning, the few things we had were put together that night, and we completed our preparations for parting for life by kissing one another over and over again, and saying good bye till some of us little ones fell asleep.’They went to live in nearby Northampton with James Davies, a cruel man who worked his slaves 18 hours a day, up to 20 hours in summer, and provided severe beatings but little food. After about 18 months at Northampton, 10-year-old Fed was separated from his mother. Davies was short of cash and he sold Fed to a ‘negro speculator’ named Starling Finney. These men were much like land speculators, buying and selling property in the hope of a profit in each transaction.

‘I looked round and saw my poor mother stretching out her hands after me. She ran up, and overtook us, but Finney, who was behind me, and between me and my mother, would not let her approach, though she begged and prayed to be allowed to kiss me for the last time, and bid me good bye. I was so stupified with grief and fright, that I could not shed a tear, though my heart was bursting. At last we got to the gate, and I turned round to see whether I could not get a chance of kissing my mother. She saw me, and made a dart forward to meet me, but Finney gave me a hard push, which sent me spinning through the gate. He then slammed it to and shut it in my mother's face. That was the last time I ever saw her, nor do I know whether she is alive or dead at this hour.’

He was taken to Millidgeville, Georgia, and sold to Welshman Thomas Stevens, of Baldwyn County, Georgia:

‘The sale took place in a kind of shed. The auctioneer did not like my appearance. He told Finney in private, who was holding me by the hand, that I was old and hard-looking, and not well grown, and that I should not fetch a price. In truth I was not much to look at. I was worn down by fatigue and poor living till my bones stuck up almost through my skin, and my hair was burnt to a brown red from exposure to the sun. I was not, however, very well pleased to hear myself run down. I remember Finney answered the auctioneer that I should be sure to grow a big-made man, and bade him, if he doubted his judgment, examine my feet, which were large, and proved that I would be strong and stout some day. My looks and my condition, nevertheless, did not recommend me, and I was knocked down to a man named Thomas Stevens, for three hundred and fifty dollars: so Finney made forty dollars by me.’Stevens was a cruel master, much like Davies had been. The forced separation from his mother had left Fed quite depressed and he did not work well, and Stevens almost beat him to death one day with hickory rods. While there Fed met John Glasgow, a free British citizen who had been inadvertently captured into slavery. It was Glasgow’s kindness and tales of freedom that inspired Fed to one day go to England. Fed knew this was ‘just over the water’, and so supposed it to be somewhere near New Orleans.

He was with Stevens for 14 years, ‘suffering all the time very much from his ill-treatment of me’, and this treatment made Fed determined to one day escape. The first time he ran away he was out a just few days before being returned. Stevens died, to the joy of all his slaves, but Fed passed to De Cato Stevens, the son, who was even worse. Floggings became more brutal, and Fed made up his mind to escape for good.

One night he hit the road which he thought would lead him straight to England, but he gave himself up after a few weeks of hardship. Stevens responded by fixing a heavy contraption of ‘bells and horns’ on Fed's head. This was made up of a circle of iron with a hinge behind and a staple and padlock in the front, hanging under the chin, to fasten it around the neck. Another iron circle sat close around the crown of the head. The two were held together by three rods of iron. These rods, or horns, stuck out three feet above the head, and had a bell attached to each.

Fed wore this device for three months. It was an agonising experience and he could only sleep in a crouched position. When it was temporarily removed one day to allow him to complete a task, Fed immediately took the chance to run away again. This time he made it as far as New Orleans but was recaptured as an unknown runaway. There was, however, some doubt about his identity in that great town so he was sent to one of the many the ‘slave pens’ to be resold. He was now using the name ‘Benford’:

‘I do not think any pen could describe the scene that takes place at a negro auction. The companies, regularly ‘sized out,’ are forced to stand up, as the buyers come up to them, and to straighten themselves as stiffly as they can. When spoken to, they must reply quickly, with a smile on their lips, though agony is in their heart, and the tear trembling in their eye. They must answer every question, and do as they are bid, to show themselves off; dance, jump, walk, leap, squat, tumble, and twist about, that the buyer may see they have no stiff joints, or other physical defect. Here may be seen husbands separated from their wives, only by the width of the room, and children from their parents, one or both, witnessing the driving of the bargain that is to tear them asunder for ever, yet not a word of lamentation or anguish must escape from them; nor when the deed is consummated, dare they bid one another good-bye, or take one last embrace. Even the poor, dear, little children, who are crying and wringing their hands after ‘daddy and mammy,’ are not allowed to exchange with them a parting caress. Nature, however, will not be thus controlled, and in spite of the terrors of the paddle and the cow-hide, the most fearful scenes of anguish and confusion too often take place, converting the auction-room into a perfect Bedlam of despair. I cannot think of it without a cold shiver. I often dream of it, and as often dwell upon it in the day-time!’Fed was sold to a new master named Jepsey James, yet another brutal man who owned a cotton plantation on the Mississippi. It was, as usual, a hard life:

‘After we reached our quarters, we got supper and turned in to rest. At four next morning we were roused up by the ‘nigger bell.’… and we all went out into the field to pick cotton from the bole, the children from ten years of age going out with us. We picked until twelve o'clock, when the cotton was weighed by a negro driver named Jeff, and we got our first meal, consisting of potatoe soup, made of Indian corn meal and potatoes, boiled up. It is called ‘lob-lolly,’ or ‘mush,’ or ‘stirt-about.’ A pint was served to each hand. It was brought into the field in wooden pails, and each slave being provided with a tin pannikin buckled round his waist, the distribution and disposal of the mess did not take long. After the meal, we set to again until night-fall, when our baskets were weighed a second time, and each hand's picking for the day told up. I had outpicked all the new hands. The rule is a hundred pounds for each hand. The first day I picked five pounds over this quantity; much to my sorrow as I found, in the long run, for as I picked so well at first, more was exacted of me, and if I flagged a minute, the whip was liberally applied to keep me up to the mark. By being driven in this way, I at last got to pick a hundred and sixty pounds a day. My good picking, however, made it worse for me, for, being an old picker, I did well at first; but the others, being new at the work, were flogged till they fetched up with me; by which time I had done my best, and then got flogged for not doing better.

After our day's picking was done, we got for supper the same quantity of ‘mush’ as we had for breakfast in the morning, and this was the only kind of food we had during the whole time I was with Jepsey James, except what we could steal.’During his three months in the slave pen Fed had picked up a great deal of valuable knowledge and tips about escaping, and after being with Jepsey James for three months, Fed once again set out on his travels. One night he took a small boat to the Arkansas side of the river and headed north, using the course of the Mississippi as a guide. He walked by night, rested in concealment during the day, eating stolen raw corn, potatoes, pine roots, and sassafras buds.

After three months living like this he reached St Louis, Missouri, bordering the ‘Free States’. Fed found helpful people there who fed him and gave him clean clothing. Not entirely a saint, he also stole some clothing from other people. He contrived to obtain a work pass, for which he used the name 'John Brown', and it was here that Fed finally took on his new permanent name.

From St Louis he again took to the road, heading north and passing himself off as a free man. On the way he discovered that there were adverts around the place offering large sums of money for his recapture, and containing accurate descriptions of him (‘sure enough my master had drawn my picture so well, that nobody could have mistaken me, unless he had been blind’). Brown, however, fell in with someone who had helped many slaves escape from slavery. He also learned that the Quakers were known to have helped the runaways, by means of the legendary Underground Railroad.

Brown was given directions to a town on the Blue River, and the name and address of one of the managers of the line. This was the first station of the Underground Railroad line.

|

| 'Underground Railroad' routes. Brown headed northeast from St Louis towards Michigan. |

The next day Brown tracked down the people he needed to find. It had now been about nine months since he had left De Cato Stevens' plantation. He was introduced to others as ‘another of the travellers bound to the North Star’ and made welcome. For the first time in his life he ate a meal sat at a table with white people. That night he slept in a bed.

‘In the middle of the night I awoke, and finding myself in a strange place, became alarmed. It was a clear, starlight night, and I could see the walls of my room, and the curtains all of a dazzling whiteness around me. I felt so singularly happy, however, notwithstanding the fear I was in, at not being able to make out where I was, that I could only conclude I was in a dream, or a vision, and for some minutes I could not rid my mind of this idea. At last I became alive to the truth; that I was in a friend's house, and that I really was free and safe.

I had never learnt to pray; but if what passed in my heart that night was not prayer, I am sure I shall never pray as long as I live. I cannot describe the blessed happiness I enjoyed in my benefactor's family, during the time I remained there, which was from the Friday morning to the Saturday night week. So happy I never can be again, because I do not think the circumstances in which I may be placed, will ever be of a nature to excite similar feelings in my breast.’

He worked at the sawmill at Dawn for about six months before securing a berth on board the Parliament, bound from Boston to Liverpool, where he arrived in August 1850. Brown immediately headed to Redruth, Cornwall, the home of his friend Joe Teague. Unfortunately, Teague had died in Boston and so never made it back to England.

Brown spent two months at Redruth, earning money by reciting his adventures to public meetings set up by his Cornish friends, including the family of Teague and his former mining workmates. They wrote of him:

‘He was employed by our Company for one year and a half; during that time we found him quiet, honest, and industrious. His object in coming to England was to see Captain Joseph Teague, by whom he was promised support. Unfortunately the Captain died in America, and J. Brown not knowing of his death till he came to Redruth, Cornwall, by that means he is thrown out in a strange country for a little support. We have heard him several times lecture on Slavery and also on Teetotalism. We hope the object he seeks will induce the sympathy of English Christians.’Brown then went to Bristol where he worked at a carpenter's shop for four weeks and then went to Heywood, Lancashire. The reasons for what was, on the face of it, a strange move remain unknown. It is possible that he met a Heywoodite elsewhere and had a job lined up for him.

Heywood by that point was a young and growing cotton town, and had recently experienced an influx of refugees from the Irish Famine. It can be assumed that African-American refugees were not a common sight there, although there had been plenty of black people around England since the previous century because the country was part of the tri-continental slave trade between Africa, Europe and the Americas. There were up to 15,000 black people in London alone by 1760, but these numbers declined somewhat after the abolition of slavery in Britain in 1807. A significant number of runaway US slaves sought refuge in England, although they often met with distrust, especially in the regional towns, and were sometimes maligned for 'living on the tramp'. Some did find a more welcoming home, such as James Johnson who arrived in Oldham in 1866 and lived there for 40 years.

Once in Heywood, Brown found employment working for John Mills, the chief builder in the town. Mills had a timber yard on York Street. Sadly, it appears that some in the local population were less than supportive of his presence and Brown did not stay long. He later wrote of this experience ‘I worked here until I found that there is prejudice against colour in England, in some classes, as well as more generally in America’.

He resolved to speak out against slavery, and ‘thought I had better make my way to London, and set about seeking the means of carrying that object out. With this view I quitted my employment, after a proper understanding with Mr. Mills, with whom I was on the best of terms’.

Brown had met the common fate of many refugees. After receiving admirable and sometimes heroic assistance during his journey to freedom, he faced racism and ignorance from new neighbours who would have struggled to comprehend the hardships of his earlier life. Fortunately, this was not the end of Brown’s travels.

Brown also envisaged an economic solution to the slavery problem, believing that the slave trade could be put out of business by establishing cotton plantations in Africa and employing locals as labourers. Brown was hoping to go to Liberia, on the west coast of Africa, where he could teach the farmers and labourers to grow cotton. He understood the process well and could even make the machinery used in dressing cotton.

As it was, he remained in London and, after marrying a local woman, made a living as a herbalist and occasional carpenter until his death in 1876.

His book Slave Life in Georgia can be read online and is recommended as a very well-written and engrossing story.

References

The slavery abolitionist cause was very strong during the 1850s. The United States was on the brink of Civil War, and in England various individuals and organisations had long argued against the trade. Brown found a willing political network eager for him to share his experiences with and build support for their cause. Obviously an intelligent and articulate man, he delivered a series of lectures detailing the slave system and his life within it. In 1855 the British & Foreign Anti-Slavery Society published his book Slave Life in Georgia: A Narrative of the Life, Sufferings, and Escape of John Brown, A Fugitive Slave, Now In England, which he had dictated to society secretary L.A. Chamerovzow. This work has been described as ‘one of the few authentic slave narratives from the Deep South’. The book sold well enough to go to a second edition and a German translation.

As it was, he remained in London and, after marrying a local woman, made a living as a herbalist and occasional carpenter until his death in 1876.

His book Slave Life in Georgia can be read online and is recommended as a very well-written and engrossing story.

'A slave is not a human being in the eye of the law, and the slaveholder looks upon him just as what the law makes him; nothing more, and perhaps even something less. But God made every man to stand upright before him, and if the slave law throws that man down; tramples upon him; robs him of his right, as a man, to the use of his own limbs, of his own faculties, of his own thoughts; shuts him out of the world up in a world of his own, where all is darkness, and cruelty, and degradation, and where there is no hope to cheer him on; reducing him, as the law says, to a ‘chattel,’ then the law unmakes God's work; the slaveholder lends himself to it, and not all the reasonings or arguments that can be strung together, on a text or on none, can make the thing right.’ (Slave Life in Georgia: A Narrative of the Life, Sufferings, and Escape of John Brown)

- John Brown, Slave Life in Georgia: A Narrative of the Life, Sufferings, and Escape of John Brown, A Fugitive Slave, Now In England, edited by Louis Alexis Chamerovzow, London, 1855.

- ‘John Brown’, Wikipedia

- ‘John Brown ca.1810-1876’, New Georgia Encyclopedia.

- FN Boney, Southerners All, Macon, Georgia, Mercer University Press, 1984.

- Jeffrey Green, Black Britain, 1858.

- Jeffrey Green, African Americans in Britain.

Comments