Blood 'Sports' in Old Heywood

Little was recorded of everyday life back in late-18th-century Heywood, but in the 1850s the newly-established Heywood Advertiser ran a couple of articles on what was still ‘living memory’ material - ‘Heywood Seventy Years Ago’. This is now more like 230 years ago. One of these articles featured some of the leisure pursuits of our forebears, and some of those pastimes clearly seemed barbaric and crude even to readers in the 1850s.

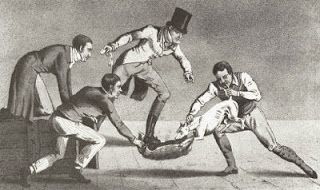

|

| Badger baiting. (Wikipedia) |

Entertainment in the village of Heywood had a bit of a rough-and-ready rural feel to it in 1780, as might be expected in what was still largely a pastoral district. The little village was only beginning to grow as the first local cotton mills opened at Wrigley Brook and Back o’th’ Moss, commencing the decades-long transformation of the village of fustian weavers into a thriving industrial mill town. There was of course no Internet, no television, no radio, and any decent form of live theatre in the district must have been extremely rare. A large proportion of the working class could not read, and most modern sports had not been invented yet. Leisure was usually to be found outside the home, and groups of men engaged in improvised physical activities invariably set against a background of gambling, drinking and animal abuse. Edwin Waugh wrote of Heywood in 1855:

'The entire population, though engaged in manufacture, evinces a visible love of the fields and field sports, and a strong tincture of the rough simplicity, and idiomatic quaintness of their forefathers, or ‘fore-elders,’ as they sometimes call them.'One popular pastime was badger baiting, in which a badger was placed inside a barrel or container, with one end knocked out to create a kind of sett for the animal. Sometimes an entrance tunnel would be added. Spectators would bet on the number of times a trained dog could make the badger come out of the box, or if it could do it all. On occasion this would be timed to see how often the feat could be done within a certain period.

Badgers are usually quite docile but possess dangerous claws and teeth, and when threatened they can be very strong and for this reason they might have been handicapped in some way, usually with a broken jaw or tied limbs. The 'sport' is of course very risky and would usually end in death or serious injury for the dog or the badger. All this was no doubt accompanied by a lot of noise and drinking from the spectators.

It has been recorded that on one occasion there were no dogs available, to the disappointment of the gathered mob, but one typical Heywoodite saved the day:

‘However, not many moments elapsed ere they were relieved out of their difficulty, for one of the company, an ardent admirer of the custom, volunteered to take the part of the dogs, and in a very short time, to the astonishment of the company present, and amidst their loud acclamations, the animal was brought forth, the man having actually caught it in his teeth, and despite the desperate exertions made by the poor creature to defend itself against such an attack it was forced to relinquish its position.’ (Heywood Advertiser, September 1854)

Cock-fighting was another popular activity. Some of these fights took place at ‘Cock Clod’ near the Queen Anne Inn. A cock-fighting clod was a round patch of earth, often surrounded by seating. These were quite common, and Cock Clod Street in Radcliffe was the location of one such venue. A Whitsun Week fight at the clod near the Queen Anne Inn was announced in a Manchester Mercury ad in 1761, with maximum weight set at 4lb 1oz, entry fee at 10s 6d, and the rather grand prize being a ‘fat cow’ worth £18.

In the 1780s there was also a cock-fighting pit in the Hardfield area, behind what is now Hornby Street. The main times of the year for this activity were Easter and Shrovetide, which was the last three days before the beginning of Lent and usually marked with games and revelries.

In the 1850s, dog fighting and cock fighting were described as being 'not uncommon' in Heywood, but 'more peculiar to the hardier population outside the towns'. The Heywood Advertiser reported in 1875 that cock fighting was still popular in the locality, particularly amongst ‘miners, colliers, squires and farmers’ who liked to bet heavily. The paper also carried a story that same year about a large crowd attending a cockfight in Ashworth.

In the 1780s there was also a cock-fighting pit in the Hardfield area, behind what is now Hornby Street. The main times of the year for this activity were Easter and Shrovetide, which was the last three days before the beginning of Lent and usually marked with games and revelries.

In the 1850s, dog fighting and cock fighting were described as being 'not uncommon' in Heywood, but 'more peculiar to the hardier population outside the towns'. The Heywood Advertiser reported in 1875 that cock fighting was still popular in the locality, particularly amongst ‘miners, colliers, squires and farmers’ who liked to bet heavily. The paper also carried a story that same year about a large crowd attending a cockfight in Ashworth.

|

| A cock-fighting pit. (William Hogarth, 1759) |

|

| Cock Clod Street in Radcliffe, Lancashire, used to be the location of cock fights. (David Dixon, Geograph) |

Bull baiting survived in Lancashire until the 1840s. This involved tethering a bull with a collar and rope and then attempting to immobilise it with dogs (bulldogs were bred for this 'sport'). The bull was sometimes enraged into action by blowing pepper up its nose. The usual course of events was that the dogs would lie flat and creep up as close as they could to the bull before rushing to bite it on the nose or head area. The bull would attempt to catch the dog with his head and horns and throw it into the air. In many instances bull-baiting was not just recreational. Until the 18th century it was actually required by law under meat-selling regulations in many English towns, as it was believed that baiting before slaughter actually improved the flesh.

|

| Bull baiting. (Samuel Henry Alken) |

|

| Pine marten. |

Hare coursing, which involved chasing hares with 'sighthounds' (such as greyhounds) that used sight and not scent to track their quarry was another popular activity that involved betting on the outcome. Dog fights and dog races were also common and were reported by the Heywood Advertiser in the 1850s, when terriers were described as being trained to hunt rats, while greyhounds were trained to race (whippet racing was established in the 19th century).

Animals were not always required for betting on street fights. Waugh wrote that in the 1850s, the 'chief out-door sports of the working-class are foot-racing, and jumping-matches; and sometimes foot-ball and cricket', along with wrestling. Men would also fight each other at a place behind the Queen Anne Inn in Heywood, the site of the 'cock clod'. This practice could well be linked to the term ‘cock’, referring to someone who is the best fighter in a particular place, making them, for example, the ‘cock of Heywood’ or the ‘cock of the school’.

‘Up and down’ (or ‘clog’) fighting has been mentioned elsewhere on this website as a pastime of men in local mining communities. Tough conditions bred tough men, and colliers were known as hard drinkers and fighters. Norden colliers were known to meet behind the Blue Ball pub and stage cock fights. Sometimes there was clog fighting, or ‘purring’, in which two miners would face each other (sometimes naked except for clogs) with their hands on each other’s shoulders, and proceed to kick each other’s shins. The winner was the first to draw blood.This was often seen as a way to settle disputes, and the betting that took place on each fight was illegal.

|

| Clog fighting. |

The popularity of blood sports concerned many in 'genteel' 19th-century society, particularly religious types such as Evangelists, and there were numerous attempts to outlaw such sports. It was not until 1835 that the Cruelty to Animals Act was passed making any sport that involved the baiting of animals illegal, although bull baiting events continued to be held in Lancashire into the 1840s.

Blood sports continue as part of British culture, although the betting element is less public. Some Heywoodites, with easy access to surrounding countryside, still go rabbit hunting or ratting on the banks of the River Roch with small dogs. Hare coursing was made illegal in 2005 but cases still come before the courts. Cockfighting is still practised illegally, but even more tragic and barbaric is the continued underground presence of dog-fighting rings, with their cruel history of stealing family pets, and it is still quite common for arrests to be made for their crime.

Fortunately the days of these events being mainstream enough to carry out in full public view in the centre of Heywood are long gone.

- Robert W Malcolmson, Popular Recreations in English Society 1700-1850, Cambridge University Press, 1973.

- Edwin Waugh, Sketches of Lancashire Life, 1855.

Comments