The Papermakers of Heap Bridge

Cotton manufacturers had limited physical space to develop their industry at Heap Bridge. One side was bounded by the River Roch and Bury, the other by steep hills and established farmland, and the prime riverside land there was already home to a thriving papermaking centre.

While cotton production did not commence in Heywood until the Wrigley Brook mill opened in the 1770s, there was a woollen mill operating at Heap Bridge by the late 16th century, and George Warburton was running a paper-making operation at Bridge Hall Mills in 1716. Warburton’s mills produced white paper, which was quite unusual as most paper made in Britain at that time was brown or wrapping paper.

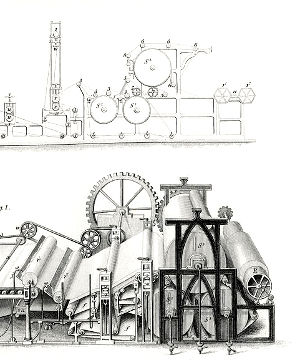

Warburton died in 1721, and by 1766 the mills were being run by Thomas Crompton. Over to the west, Bury was developing into a major papermaking centre itself, and the district contained eight of the 14 paper mills in Lancashire. The local paper boom was helped by the presence of the soft waters of the Roch, local coal mines, and the emerging cotton industry. Until the late 18th century, paper was largely made from rags, a raw material that was quite hard to find and sometimes had to be imported from as far away as Russia. However, the growing number of cotton mills in Heywood provided a steady supply of cotton waste for the paper mills, and the cotton industry also became a major customer for paper by using it for packing.

|

| Heap Bridge circa 1840s. |

The Bridge Hall Mills boomed under the ownership of the Wrigley family during the 19th century, after ‘Owd Jimmy’ Wrigley took over the mills after the death of Crompton in 1810. It was his son Thomas who did the most to expand the business, which he ran from 1846 to 1880. Thomas bought up much of the local land from the Nuttall family and, using his contacts as a railway company director, he persuaded the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway Co. to open a freight-only branch line to the paper mills by 1880. This line was used to transport raw materials in from (and the finished product out to) the main ‘Liverpool, Bolton and Bury Railway’ line (now part of the East Lancashire Railway).

Thomas Wrigley was a politically-active philanthropist, campaigning on issues such as household suffrage and educational reform, but these stances sometimes lost the company unsympathetic customers. Most of the output of the Heap Bridge Mills until the 1860s was newsprint for local and national newspapers, including the Manchester Guardian and The Times. He also wrote The Case of the Papermakers, a book calling for economic assistance for the industry.

|

| Thomas Wrigley, by George Frederic Watts. (Bury Art Museum) |

Thomas forged a close working relationship with the Grundy family, who bought the Bridge Hall estate in 1817 and ran the nearby Heap Bridge Mill. There were at least five marriages between the Wrigley and Grundy families.

Bridge Hall Mill became one of the largest paper mills in the world and stretched for half-a-mile along the banks of the Roch. In February 1915 it was the scene of one of Heywood’s worst industrial disasters when a new concrete roof with a faulty design collapsed on 20-30 construction workers below, killing eight men and injuring eight others, some of them seriously. One man later died of his injuries. The dead victims were:

William Robert Tattersall (plasterer, Longford Street, Heywood).

John O’Neill (labourer, Hall Street, Heywood).

John Sutton (labourer, Hardman’s Villas, Heap Bridge).

John Thomas Bridge (labourer, Waterfold Lane, Heap Bridge).

George William Martin (labourer, Georgiana Street, Bury).

James Yates (bricklayer, Wyndham Street, Bury).

Robert Bowker (labourer, Haslam Street, Bury).

James Turner (Deal Street, Bury).

John Crandon (labourer, Wilton Street, Heywood).

|

| Aftermath of the Bridge Hall Mill roof collapse. |

Wrigley’s company went into voluntary liquidation in 1924, but a new company called Transparent Paper Ltd renovated the mill and commenced cellulose film production there in 1928. This business continued until about 1980, and the premises were later home to Tetrosyl Ltd and Printpack Europe Ltd.

Another major paper manufacturer at Heap Bridge was Yates Duxbury & Son Ltd, which took over the insolvent Heap Bridge Paper Co. in 1882. That mill had closed two years earlier and ‘distress and actual want had come to the village’. The new operation failed within two years and Andrew Duxbury (eldest son of Yates) was declared bankrupt, but his brother Roger restarted the mill. (He was called Roger Duxbury Duxbury, thanks to a mistaken response by his godfather at his Christening). Roger was an energetic and forward-thinking businessman and made a success of the company. Typical of his thinking was the installation of electric lighting in 1887, and it is believed this was the first mill in Lancashire with this new source of illumination.

|

| Transparent Paper entrance, Bridge Hall Mills, c.1930. |

|

| Heap Bridge, early 20th century. |

|

| A Yates Duxbury cart. |

|

| Heap Bridge in 1926. |

|

| Yates Duxbury paper mill, Bury New Road, 1978. (David Dixon) |

Duxbury’s eventually ran two mills in the area, the last one closing in 1981. These mills continued to use steam locomotives on the freight line until the 1970s, and these locomotives are now part of preserved railways.

There were also several other papermakers around Heywood over time, including JR Crompton at Simpson Clough; Turner & Parker (Rochdale Road); William Henry Andrews (Rochdale Road, 1880) and Edwin Hardman (Bradshaw Street). However, much like cotton before it, the local papermaking industry eventually succumbed to changes in the manufacturing industry and of all these Heywood paper factories, only the Crompton facility is still in operation.

- A Timeline of Heywood Mills: A timeline of Heywood mills through the centuries. (Page under construction)

- The History of Crimble Mill: The history of one of Heywood's earliest mills. (Page under construction)

- The Deserted Village: Hooley Bridge in 1869: Why the once-thriving Hooley Bridge Mill and village was all but empty in the 1860s.

- The Crookedest Chimney in England: Why the Brook Street Mill was said to have the 'crookedest chimney in England'.

- Making History at Makin Mill: How the history of Makin (later Roach) Mill reflected the history of Heywood itself.

- Factory Children: Why children who worked in factories were smaller than those who didn't.

References

- John Hudson, Heywood in Old Photographs, Stroud, Alan Sutton Ltd, 1994.

- Manchester Evening News, ‘Remembering the Bridge Hall Mill disaster 100 years on’, 16 February 2015.

- RD Taylor, Yates Duxbury & Sons Ltd, Heap Bridge, Bury, Lancashire 1863-1963. (website)

- Martin Tillmans, Bridge Hall Mills: Three Centuries of Paper and Cellulose Film Manufacture, Compton Press, 1978.

- CHA Townley et al, The Industrial Railways of Bolton, Bury and the Manchester Coalfield, Part 1, Runpast Publishing, 1994.

- Thomas Wrigley, The Case of the Papermakers, Bury, J Heap, 1865.

- University of Iowa, 'European Papermaking techniques 1300-1800', Paper Through Time, 2012.

Comments

The next stage of my family history journey is to investigate these mills further. If you have any advice as to the types of records that may have been kept of the workers I would be pleased to know.

Many thanks,

Jillian Delsoldato