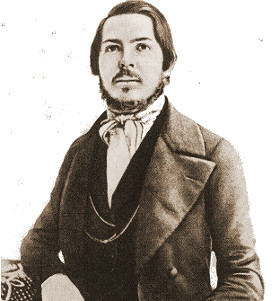

Keep the Red Flag Flying: Friedrich Engels

Among the social researchers and political thinkers who frequented the working-class towns of south-eastern Lancashire during the mid-19th-century was a young German philosopher called Friedrich Engels. What he saw there formed the basis of works that inspired the rise of Communism, leading to Engels becoming a feted hero of the Soviet Union.

And it is quite possible that Heywood played a very small role in that journey.

Engels spent a good deal of time in England during the 1840s and 1850s. He initially came to manage his father's cotton mill in Manchester, where he stayed during 1842-44. He was shocked by the appalling poverty he saw as he walked around the 'millscape' suburbs of Manchester, and took careful note of what he witnessed there. In 1844 he met Karl Marx in Paris. The two men shared common ideals and spent a lot of time working together. In July 1845, Marx stayed with Engels in Manchester for six weeks. They spent much of this time working in Chetham's Library in Manchester, researching material for upcoming publications.

Engels wrote about his observations in the 1845 book The Condition of the Working Class in England. That work contained a mention of Heywood, which he quite possibly visited in person, portraying some of the filthy conditions to be found there and in similar towns. This research was also used in the massively influential book Das Kapital that he co-wrote with Marx and was published in 1848.

Engels also visited other manufacturing areas of Britain and came to the conclusion that working people in cities all over the country suffered the same deprivations and degradations as those he had witnessed in Lancashire.

And it is quite possible that Heywood played a very small role in that journey.

Engels spent a good deal of time in England during the 1840s and 1850s. He initially came to manage his father's cotton mill in Manchester, where he stayed during 1842-44. He was shocked by the appalling poverty he saw as he walked around the 'millscape' suburbs of Manchester, and took careful note of what he witnessed there. In 1844 he met Karl Marx in Paris. The two men shared common ideals and spent a lot of time working together. In July 1845, Marx stayed with Engels in Manchester for six weeks. They spent much of this time working in Chetham's Library in Manchester, researching material for upcoming publications.

Engels wrote about his observations in the 1845 book The Condition of the Working Class in England. That work contained a mention of Heywood, which he quite possibly visited in person, portraying some of the filthy conditions to be found there and in similar towns. This research was also used in the massively influential book Das Kapital that he co-wrote with Marx and was published in 1848.

'...the most densely populated strip of country in England is Lancashire, and especially in Manchester, English manufacture finds at once its starting-point and its centre the Manchester Exchange is the thermometer for all the fluctuations of trade the modern art of manufacture has reached its perfection in Manchester in the cotton industry of South Lancashire, the application of the forces of Nature, the superseding of hand-labour by machinery (especially by the power-loom and the self-acting mule), and the division of labour, are seen at the highest point the degradation to which the application of steam-power, machinery and the division of labour reduce the working-man, and the attempts to rise above this abasement, must likewise be carried to the highest point.'

'Bolton, Preston, Wigan, Bury, Rochdale, Middleton, Heywood, Oldham, Ashton, Stalybridge, Stockport, etc., nearly all towns of thirty, fifty, seventy to ninety thousand inhabitants, are almost wholly working-people's districts, interspersed only with factories, a few thoroughfares lined with shops, and a few lanes along which the gardens and houses of the manufacturers are scattered like villas the towns themselves are badly and irregularly built with foul courts, lanes, and back alleys, reeking of coal smoke, and especially dingy from the originally bright red brick, turned black with time, which is here the universal building material cellar dwellings are general here; wherever it is in any way possible, these subterranean dens are constructed, and a very considerable portion of the population dwells in them.'

|

| Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin feature on this Soviet poster. |

Engels also visited other manufacturing areas of Britain and came to the conclusion that working people in cities all over the country suffered the same deprivations and degradations as those he had witnessed in Lancashire.

'...the houses are often so close together, that persons may step from the window of one house to that of the house opposite - so high, piled story after story, that the light can scarcely penetrate to the court beneath. In this part of the town there are neither sewers nor any private conveniences whatever belonging to the dwellings; and hence the excrementitious and other refuse of at least 50,000 persons is, during the night, thrown into the gutters, causing (in spite of the scavengers' daily labours) an amount of solid filth and foetid exhalation disgusting to both sight and smell, as well as exceedingly prejudicial to health. Can it be wondered that, in such localities, health, morals, and common decency should be at once neglected? No; all who know the private condition of the inhabitants will bear testimony to the immense amount of their disease, misery, and demoralisation. Society in these quarters has sunk to a state indescribably vile and wretched... The dwellings of the poorer classes are generally very filthy, apparently never subjected to any cleaning process whatever, consisting, in most cases, of a single room, ill-ventilated and yet cold, owing to broken, ill-fitting windows, sometimes damp and partially underground, and always scantily furnished and altogether comfortless, heaps of straw often serving for beds, in which a whole family - male and female, young and old, are huddled together in revolting confusion. The supplies of water are obtained only from the public pumps, and the trouble of procuring it of course favours the accumulation of all kinds of abominations.’ [Manchester,] 15 July 1865

Engels did make one other mention of Heywood, in a letter to Marx describing the often-disgusting food that some workers were forced to eat:

References

'The meat which the workers buy is very often past using; but having bought it, they must eat it... According to the Guardian for July 3rd, a pig, weighing 200 pounds, which had been found dead and decayed, was cut up and exposed for sale by a butcher at Heywood, and was then seized.'Related pages

- Sam Bamford and the Workers of Heywood: The conditions of Heywood workers, as described by Sam Bamford, the great Middleton Radical.

- The People’s Charter and Heywood: The role of Heywoodites in the great Chartist Movement of the early 19th century.

- The Fall of the Weavers: How the Industrial Revolution brought about the end of the once-thriving handloom weavers in Lancashire.

- Charles Howarth and the Heywood Co-op: Why a Heywoodite who was a key founder of the global Co-operative movement was featured on a Venezuelan postage stamp.

- Heywood Chartists: A list of Heywoodites associated with the Chartist Movement.

References

- Frederick Engels, The Condition of the Working-Class in England in 1844, Leipzig, 1845 (London: Allen and Unwin, 1943 edition).

Comments